(Peter Jacobsen, Foundation for Economic Education) The Federal Reserve System has come under fire in the last few months for extending itself into areas outside its Congressional “dual mandate” of stabilizing prices and maximizing employment. There are two areas where the Fed is being accused of overreaching.

The first area is economic equality. For example, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York website greets visitors with a message stating, “we are firm in the belief that economic equality is a critical component for social justice.” Senator Pat Toomey recently sent letters to several Regional Federal Reserve Banks criticizing this policy pursuit of economic equality as, “wholly unrelated to the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate.”

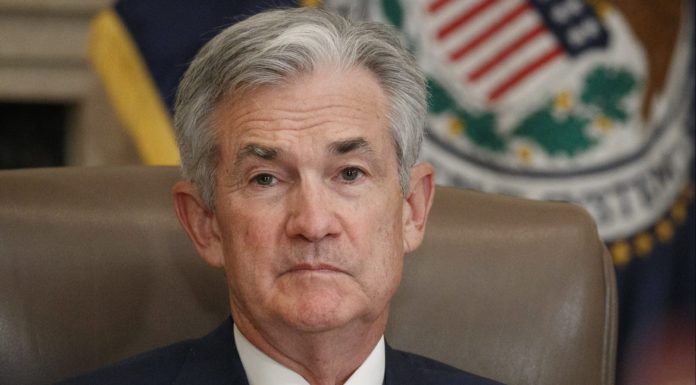

The second area, environmental policy, has also become a more central focus. Economist Alex Salter reports that the Fed recently created two climate committees and joined a group dedicated to making the financial system more environmentally focused. And, although Chairman Jerome Powell says the Fed isn’t trying to set climate policy, a report out of Reuters alleges that the Fed has begun to pressure banks to assess climate risk.

As a result of this public shift, Salter has published an open letter with 42 distinguished co-signatories expressing concern. The letter’s author and co-signers are bothered by the Fed’s mission creep, and call for the Fed to focus on monetary policy and money, rather than activism.

The Fed’s Political Dependence

While this concern is well-placed, it’s important to note that the Fed abandoning political independence is nothing new. The Fed has a long history of breaching its political independence “norms.”

Perhaps the most famous example of this was when then-President Richard Nixon pressured Fed Chairman Arthur Burns into crafting monetary policy in a way that would help his re-election. A recorded conversation between the two has Nixon laughing about the idea of political independence:

“‘I know there’s the myth of the autonomous Fed . . .” Nixon barked a quick laugh. “…and when you go up for confirmation some Senator may ask you about your friendship with the President. Appearances are going to be important, so you can call Ehrlichman to get messages to me, and he’ll call you.’”

However, the Fed hasn’t only been beholden to politicians—special interest groups also appear to have power over the Fed. After the 2008 financial crisis, a new wave of bank regulators was sent to deal with large financial institutions such as JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs. One regulator sent by the New York Fed, Carmen Segarra, released recorded conversations between herself, her supervisors at the New York Fed, and officials at Goldman Sachs.

In the conversations, Segarra is urged by her supervisors at the Fed to change her report suggesting Goldman Sachs had an insufficient policy for dealing with conflicts of interest. When she refused, Segarra was fired by the Fed.

Although being urged to change her report may be the most egregious example, the common theme in the tapes is clear: the Fed regulators seem more like partners of Goldman Sachs than watchdogs.

The takeaway is clear. The Fed has a storied history of political corruption, and this shouldn’t be surprising.

Buying Fed Policy

To understand why we should expect corruption from the Fed we need to consider the lessons of Public Choice economics.

Public Choice looks at politics as an exchange. Bureaucrats, politicians, and political appointees, for example, want things like good jobs after retirement, funding for political projects, and valuable relationships with powerful people. In order to obtain these things, these political actors may be willing to craft policies to benefit special interest groups or other politicians.

Consider, for example, the Fed. One of the powers the Fed has is the ability to print new money. When a new 100 dollar bill is printed, the first person to receive the new money will be able to use it to buy real goods and services. If they buy a TV, for example, the new 100 dollar bill goes to the person who sold the TV. However, as the new dollar bill is spent more and more, the increased demand it creates leads to higher prices, everything else held constant.

So while the first people to get the new money get a good deal, it leads to higher prices for everyone else. Inflation is like a hidden tax on whoever gets new money after the prices have risen. Receiving new money first, then, is a privilege that some may be willing to pay for. If it only costs you $90 to lobby the Fed for a new 100 dollar bill, you come out $10 richer.