(Scott T. Cross, Mises Institute) Recently, anyone who pays attention to current events has been assaulted with the news that both the Hollywood actors’ and writers’ unions are striking simultaneously for the first time since 1960. Workers for UPS also recently reached a deal with their employer after threats of a nationwide strike by the Teamsters union.

Although many may think that unions are a thing of the past and are no longer relevant, they clearly remain both a political and economic force to be reckoned with. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, approximately 10 percent of workers in the United States are members of some kind of union. Despite the fact that membership is down substantially since the later part of the twentieth century, unions still represent a sizable demographic of the workforce. Unfortunately, the subject has become politicized, so it is helpful to remember and analyze what the actual effects of unionism are on the economy and not become bogged down in partisan accusations of greed and maliciousness.

In a free market, employees and employers come together to exchange services for wages. Employees compete to see who is willing to provide his services for the lowest price. Conversely, employers compete with each other to see who is willing to pay the highest price for the offered labor.

Both parties must try to analyze the market accurately though. If an employer offers too small a wage to his workers, other employers will outbid him, and he will be forced to either increase his offer or eventually go out of business because no one will work for him. Similarly, if a laborer refuses to work except for an exorbitant wage, other laborers will undercut him. He will be forced to either accept a lower wage or be driven from the market entirely, with less picky laborers being hired and taking his place.

Although employees compete with each other and employers compete with each other, employees and employers cooperate with one another, with one willingly accepting an agreed-upon wage from the other in exchange for his labor. This exchange naturally occurs in a market economy as a result of individuals being allowed to negotiate and enter into the exchange free of coercion.

Ludwig von Mises pointed this out in his seminal work Human Action: “The market wage rate tends toward a height at which all those eager to earn wages get jobs and all those eager to employ workers can hire as many as they want.”

Mises explains that this is a completely organic process that, if permitted to play out without governmental intrusion, would result in both employers and employees being content—where everyone wanting to buy could buy and everyone wishing to sell could sell.

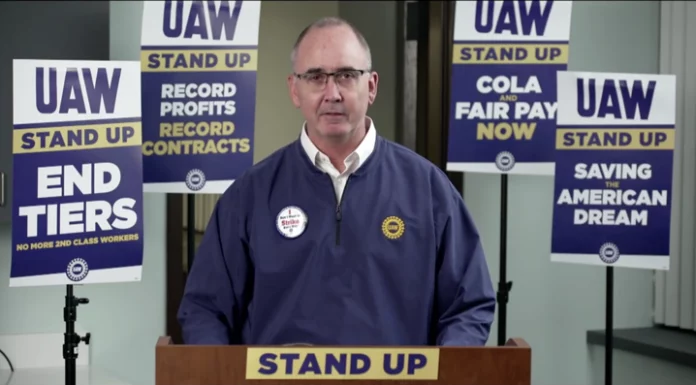

Labor unions introduce an interesting variable into the mix. Members of these unions engage in what is known as collective bargaining. This entails a group of employees agreeing not to undercut each other and to, instead, conjointly demand an artificially high wage above the market price.

If their demands are not met satisfactorily by the employer, the union members go on strike, refusing to work and often assembling outside their employer’s business, forming a “picket line.” This picket line is a boundary that the striking workers form where they attempt to garner support from the community by explaining why they are striking and often intimidate those who are coming to take their place in the workforce.

In early American history, unions were not overly popular and were actually in many ways frowned upon. The quasi-libertarian sentiments of a nation that idealized individualism and had prompted the United States’ secession from tyrannical England was not overly sympathetic to those who wished to band together to force their perceived self-worth down the throats of their employers, especially when this necessarily resulted in the least-productive workers benefiting the most. It seemed much more logical that people would be treated as individuals, rather than a collective blob of workers, and paid according to the quantity and quality of the work they each completed.

This all began to change during the Progressive Era, toward the beginning of the twentieth century, with government increasingly working hand-in-hand with the labor unions, tilting the scales in their favor during negotiations.

The reason unions experienced and still enjoy this surge in popularity seemingly defies understanding. Unlike other deviations from the free market, union incursions have very obvious effects that are often boasted about proudly by union members and felt almost immediately by the adoring public.

One of the primary reasons people join unions is for the benefit of receiving a higher wage. Logically, this will increase the costs of producing the product they are manufacturing and will also bring the price of labor above the market clearing price, resulting in a surplus of labor, which is synonymous with unemployment.

If they do not receive this increase in wages, the union’s members go on strike, refusing to work and foisting their perceived hardship on others by not producing a consumable product, often intimidating and criticizing those who come to take their place in an effort to ensure no goods enter the marketplace from their place of work. The Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, the Hollywood actors’ union, and the Writers Guild of America West, the writers’ union, is currently demonstrating this to full effect, with dozens of movies and television shows being delayed or having their production shut down as a direct result of the strike.

If the union is successful, the heightened price of hiring someone not only makes it more difficult for individuals to get a job in a unionized environment, but it also leads to the people who didn’t make it into the higher-priced union job seeking employment in jobs that are not unionized. This necessitates an increase in the labor supply at these places and the lowering of their wages.

However, anyone who points out these basic economic facts is completely vilified as “unfeeling” toward the working class. Quasi-Marxist accusations are put forth that the employers are just greedy capitalists, intent on exploiting the blue-collar population to line their pockets, and that all workers should—in the words of Karl Marx—“unite” against anyone who opposes unions in any way, for they are accomplices to the oppressors of the working class.

Furthermore, unions have positioned themselves as strong proponents of minimum wage laws and protectionist policies, explaining that they are fighting for all workers, not just the unionized. These policies shield unions from free market competition, force consumers to pay higher prices for lower-quality goods, and stunt both economic and technological growth. Recent examples of this include union opposition to self-checkout kiosks in various stores and calls for artificial intelligence to be regulated, all with the justification of protecting workers.

This all promotes an “us versus them” mentality, with the general public gullibly supporting the unions’ march toward government control. The public and news organizations do not bat an eye when they hear that unions have achieved a higher wage, raising the price of a product, or that a union is going on strike, and the public won’t be able to enjoy a movie they had been looking forward to seeing. Instead, anger is directed at the employers, who should apparently just appease the poor workers and heap unearned wage increases on them.